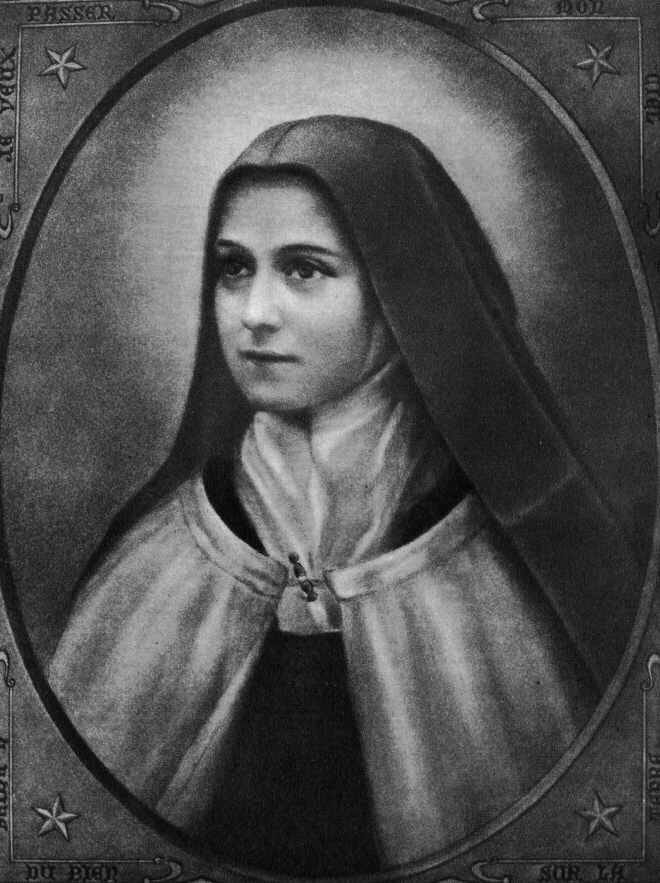

A Sermon for the Feast Day of St. Therese of Lisieux

Gracious Father, who called your servant Therese to a life of fervent prayer, give to us the spirit of prayer and zeal for the ministry of the Gospel, that the love of Christ may be known throughout all the world; through the same Jesus Christ, our Lord. Amen.

Today is the feast day of St. Therese of Lisieux.

Therese isn’t very popular in Episcopal circles, but the Catholic women I know tell me that she was an important part of their faith formation. I first learned about her in 2021, from a lay preacher at my summer internship.

But, good news for all of us! Therese was officially added to the Episcopal festival calendar in 2022.

I like to think of her as my unofficial patron saint, because her feast day was the day before my ordination to the priesthood last year. But that was just the icing on the cake. Therese keeps showing up in my life. So much so, that I was surprised that I hadn’t already talked about her in a sermon!

In my experience, sometimes the saints seem to follow us around, and it’s a good idea to try to figure out what they’re trying tell us. So, think of this sermon as a bit of sleuthing on my behalf.

What is Therese trying to tell us?

—

Before I get there, I just want to say that the lives of saints are interesting to me, because even though they get lumped together as VIPs in God’s kingdom, their stories are really more about how GOD works in our messy humanity.

And no one story follows the same path. Some saints are from wealthy families, others come from poverty. Some are known for their mystical visions, and others for their peculiar ways of life. Some are famous during their lifetimes, and others become popular after their deaths.

But all of them have one thing in common: at some point, they get infected by the Jesus bug, and it leads them to places they never could have imagined.

Through danger, illness, abandonment, and every kind of complication, the saints become saints, because no one can deny that God is working in their life.

In that sense, sainthood directs us to notice God at work in every kind of person and in all kinds of ways.

The lives of the saints show us that faithfulness, and not status, is what matters to God.

—

So, what’s Therese’s story?

Therese became a discalced Carmelite nun in 1888. She was 15 years old.

(The word “discalced” literally translates to “without shoes.” The discalced Carmelite order practices extreme simplicity of living. They devote their lives to prayer and contemplation.)

Therese was born into a wealthy merchant family, but things were far from good. When she was 4 years old, her mother died of breast cancer. As a young child, she was frequently bullied by a girl at her school. When her older sister entered the convent, Therese began to suffer from tremors and other anxiety symptoms. If she were alive today, we would probably say she lived with depression and anxiety.

Before becoming a nun, Therese suffered from years of spiritual doubt, as she continued to grieve the death of her mother. She describes the hopelessness she felt in her autobiography. One Christmas Eve, she sat down to open presents, and was overcome with what she describes as the “joy in self-forgetfuless.” She was finally able to move forward.

Therese entered the convent shortly after.

In the convent, she struggled to make friends. She described these experiences as deeply painful. But she was determined to pray for those who persecuted her, and even spent extra time with people she didn’t like.

Her humility and endurance in the face of difficult relationships puzzled people. But it ended up shaping her life toward sainthood.

—

Therese is best known for developing a spiritual practice called “the little way.” When you walk the little way, you think of each little act as an offering to God. You don’t worry about trying to impress others, or apologize for not being perfect.

Therese described it this way:

“The only way I can prove my love is by scattering flowers and these flowers are every little sacrifice, every glance and word, and the doing of the least actions for love.”

Because of the little way, Therese had no patience for ego-driven choices. She rejected opportunities to rise through the ranks at the convent, and focused on reading the Gospels, instead of the popular theology of the day.

Over time, she came to understand that her shortcomings “did not offend God.” She said: “My way is all confidence and love.”

Therese died from tuberculosis at the age of 24. But thanks to her spiritual autobiography, many people were compelled to practice the little way.

—

Now that I’ve said all that, I have to admit that I have been avoiding Therese.

That’s because, in Catholic imagery, Therese is often represented as a dainty young woman surrounded by pink roses. For more than a century, the strength of her life has often been misrepresented by the church.

Instead, she has served as a symbol of female meekness and juvenile ignorance. She has been depicted as the opposite of empowered.

On the surface, she is everything I reject in my life, as a Christian and a priest, who happens to be a woman.

If the churches I grew up in respected the saints, I’m sure I would have been force-fed Therese as a way to keep me in line. As a way to remind me that a woman’s place is among chubby-cheeked babies, humming a sweet hymn, and wearing a pink ribbon in my long hair.

But I think this is part of the reason Therese has been following me around.

Not because I need to learn a lesson about femininity from Therese. But, so I will be forced to soften that judgmental impulse to condemn her for boxing me in.

Therese’s personality and teachings may have aligned with the gender politics of the church, but she wasn’t boxing anyone in! Therese was the way she was, because God had transformed her grief and rejection into a path to spiritual liberation.

She lived and ministered exactly as she was, because she was confident that Christ loved her and fully welcomed her. She was actually fully empowered, because she wasn’t trying to impress anyone.

Her gift to the church is not that she was quiet and sweet, though there’s nothing wrong with those traits.

It is that she spent her ministry being honest.

—

In the Gospel today, Jesus reminds the chief priests and elders that their intellect and fancy titles don’t give them special access to the Kingdom of God.

No, the inheritors of the Kingdom are simply the faithful ones. They are the prostitutes and tax collectors, who don’t deny their need for grace. Like Therese, they understand that their “shortcomings do not offend God.”

Those who have lived with grief, illness, abandonment, and bullying don’t really have the luxury of putting on airs. When you’ve been through Hell and back, you no longer have the patience to pretend like everything’s ok.

This radical honesty leads to incredible clarity. Those who have lived in the valleys of life are often the first to notice that Jesus is the Savior. They are the first to believe that the Kingdom of God is near.

While the privileged and unburdened ones are talking the talk, the survivors are actually walking the walk, even if they come limping.

There are so many who have walked the walk, along the little way. Some of them are in this room today.

And, through your little acts of kindness, patience, and endurance, you have been invited into the Kingdom of God. You are taking part in the healing of the world.

—

So, what is Therese trying to tell us? What is Jesus trying to tell us?

Maybe…Keep the faith. Live your life with the confidence that Christ loves you, that he welcomes you for who you are, and has a way of transforming your suffering into love.

Believe that every small step toward Christ builds the kingdom. Your faithfulness makes a difference, even if nobody else notices. You may not have much to give, but YOU are enough.

You are not being asked to contort who you are to fit the expectations of the world. You are being invited into the fullness of all Christ made you to be.

Walk the little way.